Identifying Your Critical Workforce

Ruin to recovery

We all recognise the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon our organisations. Supply chains, both upstream and downstream were interrupted and the lockdown restricted both our employees and our customers. Operating models shifted to respond to this disruption and our ways of working were transformed quickly to enable distanced working. Some industries have seen a surge in revenues whilst others have faltered; customers have been lost and new ones found. Our organisations are very different now from what they were in January and our business plans have fundamentally changed.

Despite the unprecedented economic damage, we are now seeing green shoots; a comparison by HM Treasury of independent forecasts point to a 14.3 percent rise in GDP in the third quarter of this year[i]. As lockdown restrictions have eased, retail sales have bounced back with July’s volumes up year-on-year[ii]. With advertised vacancies are on the rise[iii] it is clear that success lies in organisations having the right workforce for the road ahead.

Where do we start?

The challenge for many looking to create the right workforce is working out where to begin. Creating a workforce plan for organisations in the tens and hundreds of thousands is not for the fainthearted and, if maturity in workforce planning and analytics is low, may take a long time to create. Instead, we prioritise workforce planning for the areas that will generate the greatest benefit for our organisation.

Workforce segmentation

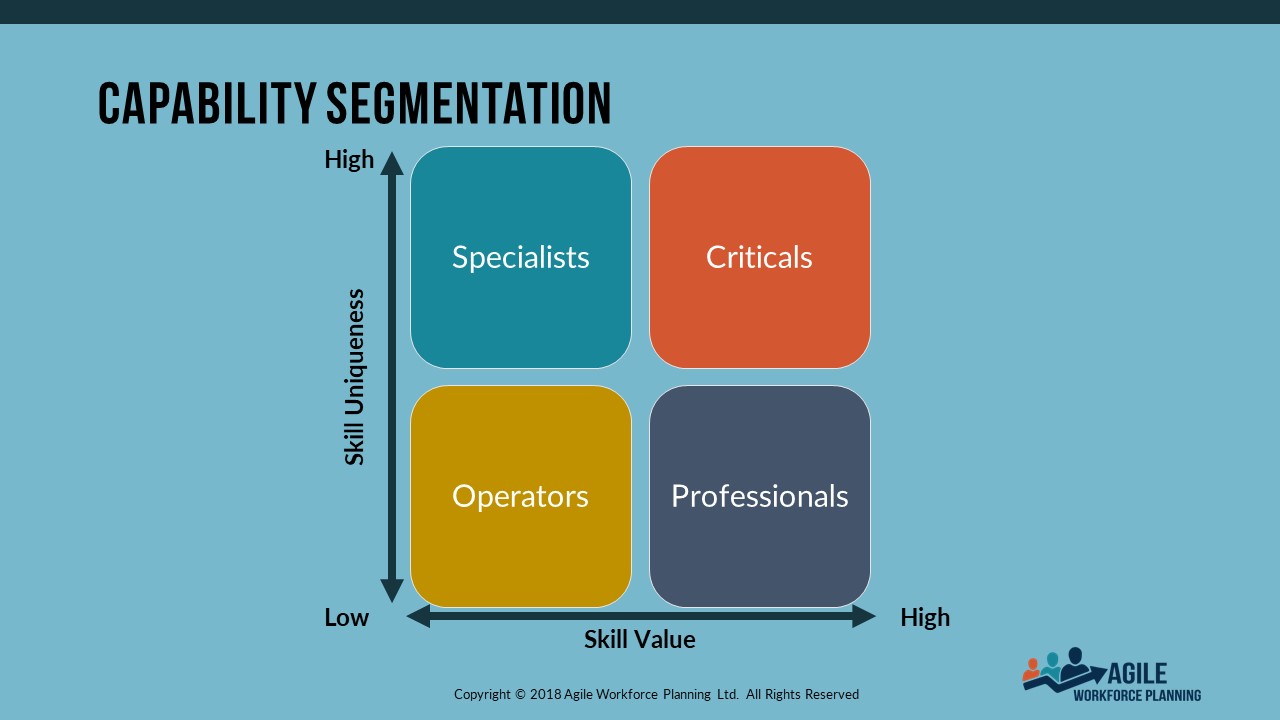

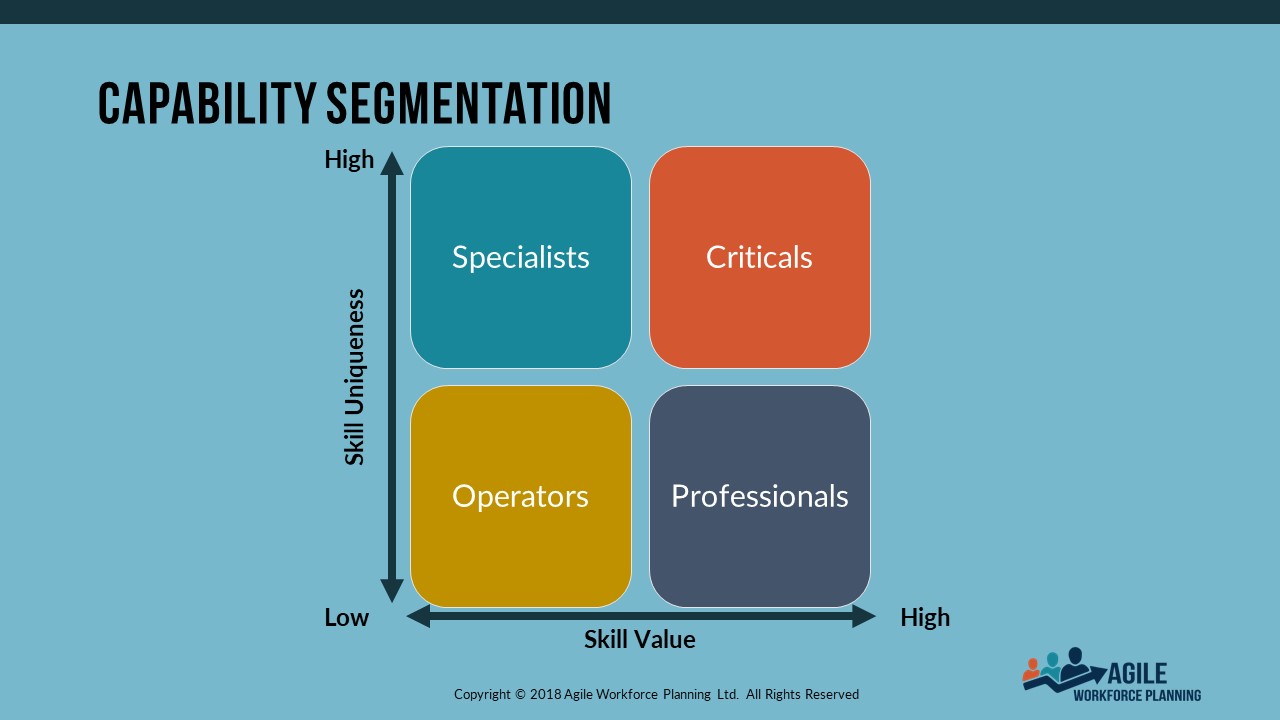

Workforce segmentation is a vital step to better understand our people and prioritise roles for action. One of the simplest ways to do this is in line with the framework for human resources architecture, devised by Professors David Lepak and Scott Snell[iv]. An adapted version of this framework, below, proves highly effective for segmentation of the workforce based on their capabilities.

It separates the workforce into four quadrants based on the uniqueness and value of workforce segments to the organisation.

- Specialists are those roles that are unique to the organisation or the industry and tend to require expertise in exclusive technologies or processes. As a result, performance levels are fairly uniform; once competence is achieved there is little or no variability in the value that is generated. A great example are drivers on the London underground: their high levels of training are focused on operating the tube trains and do not transfer to a bus. Provided they are competent and safe, a driver cannot operate in the underground in a way that creates greater or lesser value to passengers than their peers could generate.

- Professionals are very much the opposite of specialists and are common across all industries. Great examples are those who work in HR, finance and project management, where professional standards are set by bodies that sit outside the organisation, such as CIPD, ACCA and APMP. These knowledge workers rarely find themselves working within constrained processes; as a result, the performance and value generated between two different professionals can differ greatly.

- Operators are the administrative and manual roles that exist within our organisations. They include the entry-level roles that might be the first step towards a specialist or a professional role. Though their capabilities are common across industries, they remain guided heavily by processes, which means there is little variability in performance and value.

- Criticals share many characteristics of both specialists and professionals, which is often the background of those workers. Like specialists, these roles will have capabilities that are unique to the organisation. However, just like professionals these are knowledge workers where individual performance can drive exponential value for customers and the organisation. These roles are what are often known as the “A Positions” within a business, “those in which top talent significantly enhances the probability of achieving the business strategy” [v].

What is the importance of identifying critical roles?

For many organisations, their identification of critical roles often follows hierarchical lines. They start with the CEO and work their way down through their direct reports, perhaps to CEO minus 2 or even CEO minus 3. However, it is vital to recognise that criticals are not exclusive to the top tiers of the organisation.

An article by McKinsey & Company[vi] highlighted the example of a CEO who, in pinpointing criticals, had neglected to identify an account manager for a key customer. It entailed high levels of responsibility and demanded a rich mix of technical and interpersonal skills from a role that needed to respond adroitly to changing client needs. For a relationship vital to current and future growth, this account manager was critical to achieving the business strategy and a source of both current and future comparative advantage.

Not tracked as a critical role, the firm were unaware of the increasing dissatisfaction of the high-performing incumbent. When the account manager suddenly accepted a job at another company and announced her resignation, her superiors were caught off guard. Not tracked closely enough, they had missed the opportunity to retain her and had no form of succession plan to ensure continuity for their client. As a result, performance suffered whilst they tried to secure temporary cover for the role.

Which are our critical roles?

There is no predefined list of critical roles for organisations; like fingerprints, they are unique to values, strategy and objectives of the business. Indeed, the critical roles that you may have identified before the pandemic may not necessarily be the case now. Criticals will always meet at least one of the following criteria:

- They are critical to achieving the business strategy; either in the design or the execution of that strategy. They are the roles where the loss of a high-performing incumbent could result in a business disruption or a loss of revenue.

- They are a source of the organisation’s current comparative advantage; their capabilities provide differentiation from competitors that enables them to provide a service for customers that is either unique, or otherwise faster or at lower cost

- They are a source of the organisation’s future comparative advantage; their capabilities will enable the organisation to excel in the future in comparison to competitors. This means that some critical roles may not yet exist.

What next?

Once you have identified your criticals, look to the following:

- Check alignment. Is the execution of the tasks within those critical roles still relevant? If strategies and objectives have changed, it is vital to ensure these are aligned. Though criticals are imperative to success, they can steer the organisation off-course if not properly aligned to the new direction.

- Prioritise retention. The pandemic has been a challenging time for all of us, which may well have fallen significantly upon those in critical roles. Possible increased levels of dissatisfaction are coinciding with increased hiring as businesses look towards recovery; those who are vital to your organisation will be at a higher risk of poaching from other companies. Take an individual interest in your criticals and prioritise activities to improve their wellbeing and incentivise their continued employment.

- Reimagine work. What work being done by criticals could be done differently, which would make their lives easier and drive greater value for your organisation. Strip out repetitive work and examine where robotic process automation (RPA) could replace or augment that activity. Could lower value work, that acts as a mental drain, be moved elsewhere to allow criticals to focus their efforts.

- Plan for succession. The only guarantee in life is that, eventually, a worker will leave their current role; they may leave the organisation or secure promotion elsewhere. You need a plan in place to ensure continuity of service and, given the high level of uniqueness and value of the capabilities of criticals, this cannot be done on receipt of resignation. Look at multiple options for succession and develop these to ensure your critical roles endure.

[i] HM Treasury (2020) Forecasts for the UK economy (19 August) https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/forecasts-for-the-uk-economy-august-2020

[ii] ONS (2020) Retail sales, Great Britain: July 2020 (21 August) https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/retailindustry/bulletins/retailsales/july2020

[iii] ONS (2020) Labour market overview, UK: August 2020 (11 August) https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/august2020

[iv] Lepak, D P & Snell, S A (1999) The human resource architecture: toward a theory of human capital allocation and development, The Academy of Management Review, 24 (1), pp 31-48

[v] Becker, B, Huselid, M & Beatty, D (2009) The Differentiated Workforce, Harvard Business Press, Boston

[vi] Barriere, M, Owens, M & Pobereskin, S (2018) Linking talent to value, McKinsey Quarterly, 2018 (2) , pp 36-44

This article originally published September 2020 by Blue Arrow

Adam Gibson is a global leader in Workforce Planning, creator of the Agile Workforce Planning methodology and a popular keynote speaker. He has successfully implemented and transformed workforce planning and people analytics in businesses across both the public and private sector. As a consultant, he advises company executives on how to create a sustainable workforce that increases productivity and reduces cost; he is also the head of CIPD's workforce planning faculty.